by Joshua Jekot

Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) injury is a common sporting injury with an incidence rate between 30-78 per 100,000 persons each year. Australia has the highest reported rate of ACL injuries across the world. ACL injuries have been increasing within Australia, in particular in those under 25 years old, increasing greater than 70% over the last 15 years (Zbrojkiewicz et al., 2018)

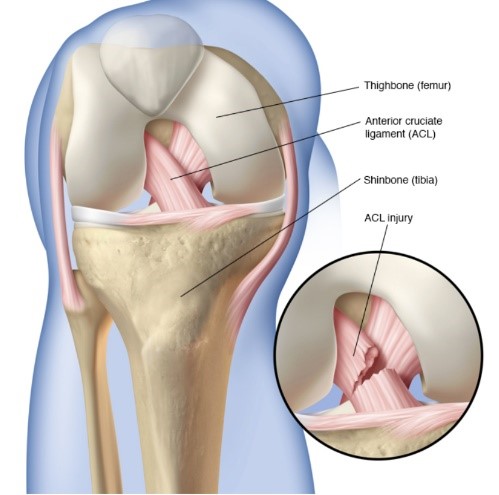

What is the ACL?

The Anterior Cruciate ligament is a ligament which sits deep in your knee and prevents your thigh bone (femur) from moving forwards on your leg bone (tibia). The ACL also assists in preventing excessive rotation of your knee joint inwards and outwards. The ACL helps to provide stability for the knee.

Surgery:

The most common treatment for ACL rupture is an ACL reconstruction. This is where they take a donor graft from the patient, most commonly the hamstring or patella tendon and use this to create a new ACL. Following surgery, the patient will undertake an extensive rehabilitation program often returning to sport between 9-12 months post-surgery.

Do I need surgery?

ACL reconstruction is the favoured method for treating ACL injuries withing Australia, being the country with the highest rates of ACL repair globally. However, as more research emerges it is becoming apparent that immediate ACL reconstruction is not always required. The KANON trial was a large high-quality trial looking at surgical versus rehabilitation alone for the management of ACL injuries (Frobell et al., 2010). The study outlined several key findings which can help patients with their treatment decisions. The KANON trial was a 2 year follow up Randomised Control Trial (RCT). At 2 years follow up there was no differences between the surgical group vs the rehabilitation group regarding patient reported outcomes, return to sport and knee function. Furthermore at 5 years follow up, there was no significant differences between surgical versus rehabilitation groups for Knee function, quality of life, physical activity levels, osteoarthritis (OA) changes and meniscal surgeries (Ericsson et al., 2013). Additionally, there is emerging evidence of spontaneous healing of the ACL following non operative management. Spontaneous healing was associated with a favorable clinical outcome compared to the non-healed, delayed ACL reconstruction and early ACL reconstruction (Filbay et al., 2023).

Who is suitable for non-operative management?

Many factors need to be considered when deciding if surgery or non-surgical is the best option post injury. Firstly, the prevalence of concurrent injuries to the structures in the knee at the time of injury such as PCL injury, MCL, longitudinal meniscus injury or significant cartilage injury. These concurrent injuries may further impact on the stability of the knee and need to be considered. Additionally Fitzgerald et al looked into determining ‘Copers’ and ‘Non Copers’ following ACL injury (Fitzgerald et al., 2000). They were defined as:

Coper: Someone who can cope with ongoing rehabilitation after ACL injury

Non-Coper: Someone who experiences symptoms and instability upon their return to pre-injury activities.

Fitzgerald et al (2000). screening tool included four one-legged hop tests; single leg hop for distance, single leg triple hop, single leg triple crossover hop, and the 6-m timed hop test. These tests were used in combination with the incidence of the knee giving way, a self-report functional survey (Knee outcome survey-Activity of Daily Living Scale—KOS-ADL and a self-report global knee function rating. Patients who presented without concomitant injuries who achieved a minimum score of 80% limb symmetry on all hop testing, >80% on the KOS-ADLS, >60 on the self-report of knee function, and ≤1 subjective report of knee giving way were considered “potential copers” and may benefit from rehabilitation alone.

Conclusion:

There is emerging evidence that people can recover quite well post ACL injury with rehabilitation alone. It is important to have a review with your physiotherapist to determine if you would be an appropriate candidate for rehabilitation alone and to commence your rehabilitation journey.

Key Take Aways:

- For the appropriate individual, rehabilitation alone can have similar outcomes to surgical management of ACL injury

- Having and ACL reconstruction DOES NOT reduce the risk of Osteoarthritis

- You can return to pre-injury levels of sport without an ACL Repair

- A comprehensive rehabilitation program is paramount for both ACL reconstruction and non-operative management.

References

Ericsson, Y. B., Roos, E. M., & Frobell, R. B. (2013). Lower extremity performance following ACL rehabilitation in the KANON-trial: impact of reconstruction and predictive value at 2 and 5 years. British journal of sports medicine, 47(15), 980-985.

Filbay, S. R., Roemer, F. W., Lohmander, L. S., Turkiewicz, A., Roos, E. M., Frobell, R., & Englund, M. (2023). Evidence of ACL healing on MRI following ACL rupture treated with rehabilitation alone may be associated with better patient-reported outcomes: a secondary analysis from the KANON trial. British journal of sports medicine, 57(2), 91-98.

Fitzgerald, G. K., Axe, M. J., & Snyder-Mackler, L. (2000). A decision-making scheme for returning patients to high-level activity with nonoperative treatment after anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 8, 76-82.

Frobell, R. B., Roos, E. M., Roos, H. P., Ranstam, J., & Lohmander, L. S. (2010). A randomized trial of treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tears. New England Journal of Medicine, 363(4), 331-342.

Zbrojkiewicz, D., Vertullo, C., & Grayson, J. E. (2018). Increasing rates of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in young Australians, 2000–2015. Medical Journal of Australia, 208(8), 354-358.